In antiquity Alexandria was second only to Rome. The north African port was home to a famous library and one of the seven wonders of the world, the lighthouse Pharos. Both are long gone, but you can see some remains of the physical library.

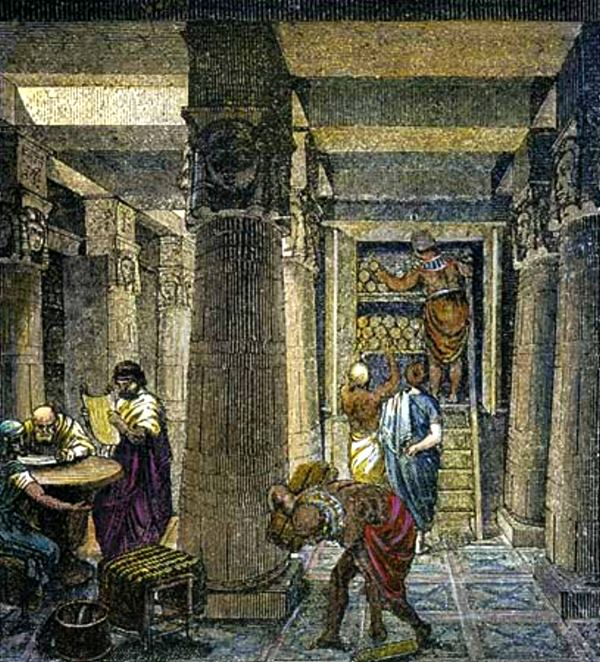

Visible remnants of the library at Alexendria, Egypt.

That was about all I thought of it until reading Stephen Greenblatt’s Pulitzer prize-winning The Swerve, which recounts the discovery in 1417 of a poem by Lucretius believed lost. This can sound like dry stuff but the story is vividly, almost luridly told, Greenblatt arguing that this is a moment to which the modern world can trace its origin.

His passage on Alexandria fits into a larger discussion of how all that ancient learning got lost in the first place – fire and intolerance directed at the books themselves, but also sheer time, random periods of social unrest, excessive scrolling and unscrolling, and bookworms.

In the center of the city, at a lavish site known as the Museum, most of the intellectual inheritance of Greek, Latin, Babylonian, Egyptian, and Jewish cultures had been assembled at enormous cost and carefully archived for research. Starting as early as 300 BCE, the Ptolomaic kings who ruled Alexandria had the inspired idea of luring leading scholars, scientists, and poets to their city by offering them life appointments at the Museum, with handsome salaries, tax exemptions, free food and lodging, and the almost limitless resources of the library.

Maybe it’s just because I work in one, but this sounds to me a lot like a university, down to the institution of tenure – but a good dozen centuries before the medieval European institutions we usually cite as our beginnings.

The library at Alexandria as it may have looked.

And these weren’t merely repositories of knowledge: like our own, they were also expected to generate it:

The recipients of this largesse established remarkably high intellectual standards. Euclid developed his geometry in Alexandria; Archimedes discovered pi and laid the foundation for calculus; Eratosthenes posited that the Earth was round and calculated its circumference to within 1 percent; Galen revolutionized medicine. Alexandrian astronomers postulated a heliocentric universe; geometers deduced that the length of a year was 364 1/4 days and proposed adding a “leap day” every fourth year . . .

. . . The Alexandrian library was not associated with a particular doctrine or philosophical school; its scope was the entire range of intellectual inquiry. It represented a global cosmopolitanism, a determination to assemble the accumulated knowledge of the whole world and to perfect and add to this knowledge.

Who knew? Probably many who read this blog, but I found it a surprising and reassuring sign of something old and essentially human.

However bleak things get, or overrun with fire, unrest, and digital bookworms, we apparently feel driven to systematically and cooperatively keep track of what we know, and add to it.

Image credits: pegnsean.net, thelivingmoon.com

I love this!! Wonderful insight — thank you!

Sure – and thanks for stopping by!